Going Against the Flow

Developers like to talk about being in a state of flow. This is when time just seems to fly by and you’re writing more code in a few hours than you do in several days when you’re not “flowing”. While I think flowing can be postive, it often can do more harm than good if going on for too long.

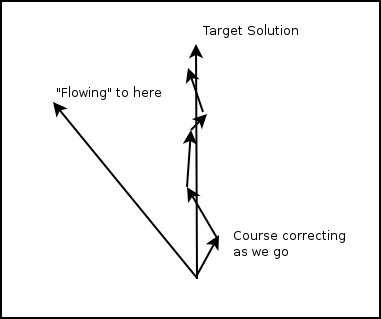

In the past I would complain that the environment around me kept me from the flow. I would look forward to the quiet times in the office when I could zone out for hours and complete some wild and crazy code I was working on. Many times I would return the next day and realize that I could have done it simpler, or there were many other aspects of the problem that I didn’t take into consideration. One of the biggest complaints about flow is that it takes a long time to get into that state. How can we minimize this time, and keep these flows shorter?

This leads me to spiking. Getting into a flow can be useful when performing a spike. It can reduce the spike time, but is it really possible to flow when working on something you don’t have any clue about?

When programming solo I try my best to always practice the pomodoro technique. There have been so many times that the break (and I try to be disciplined about stopping when the timer goes off, even when I’m in the middle of something) introduces new ways of tackling the problem.

When pairing I experience similar gains with breaks. I never considered this technique when pairing, because I always thought that the practice already mitigated the risks I mentioned earlier. That may be true, but thanks to Paul Daigle, I found that it was just as effective when pairing. It’s even better because you have someone to reflect upon the pairing session with. A quick time away from the code is a good time to recall what problem you’re actually trying to solve and whether or not the direction you’re going is actually going to lead you there.

If you’re leading a technical team and you see everyone glued to their monitors and typing franctically, you might think that they are “flowing” and working at a heightened level of productivity. Think again, they could possibly be racing towards the wrong direction. A team that’s moving around, going for walks, taking 5 to do a tabata to me is a sign of a more switched on team.